From an outside perspective, Director Bong Joon Ho’s historic win at the 2020 Oscars signaled a critical shift in the Republic of Korea’s film industry. Bong, winning Korea’s first four Oscars that night, was seen as a hero of Korean cinema, bringing it to the global spotlight and opening the door for dozens of Korean directors after him. President Moon Jae In himself applauded the film for its historic win and promised a new commitment to invest in Korean cinema. However, we cannot look at Bong’s victory as the start of a completely new tradition of Korean cinema. Rather, it is the culmination of decades of the work of various auteurs, an occasionally strained relationship with the Korean government, and the slow but steady exposure of Korean cinema abroad.

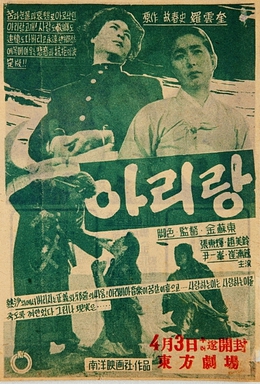

The official start of Korean cinema is often marked with the release of Fight for Justice (kor: 의리적구토) in 1919. This film was actually a kino-drama (kor: 연쇄극), a mixture of theatrical performances with on-screen elements. The film was the story of a man whose wealth was stolen from him, forcing him to live under oppressive control. Koreans of the time could absolutely connect the struggle of the protagonist with the exploitation and domination of their country under Japanese colonial rule. The relationship of this film to the plight of Koreans is strengthened by its release occurring in the same year as the March 1st Independence Movement. This film’s status as the progenitor of Korean cinema is important in itself, but its relationship to the society within which it was created is the beginning of a long history of citizens using film as an act of rebellion, protest, and social change. This trend would continue with the release of Arirang (kor: 아리랑) 1926, which would directly critique the oppression Koreans faced under Japanese rule and inspire a nationalist sentiment among Koreans at the time. Sadly, many films produced during Japanese Colonialism and the Korean War were destroyed or lost, so most early films exist only through secondhand accounts.

Arirang, 1926

The years following the Korean War saw a massive expansion of the film industry. Film production shot up drastically, and viewership during this period reached the hundred millions. A standout film from this period is Director Kim Ki Young’s 1960 film The Housemaid, which shocked audiences with its portrayal of a maid tearing apart a family by seducing the husband. However, this period of commercial success was also defined by a strong government crackdown on film production. The Park Chung Hee government consolidated major movie studios and placed heavy censorship on films at the time, meaning the potential for even larger artistic growth was stifled by government interference. At this point, the government was incredibly sensitive about the spreading of communism, so all content that could be interpreted as pro-communism or in support of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea would be altered or banned. The foundation of the Korean Motion Picture Promotion Corporation (kor: 영화진흥위원회) in 1973 was meant to further development of the Korean film industry, but its productions were saturated with pro-government messaging and social propaganda. A defining aspect of Korean cinema was its ability to freely discuss social issues and the daily life of its viewers, so these sanitized depictions of Korean society were unappealing to many viewers.

There was a promising shift in the 1980s with the authorization of independent filmmaking once again, however this hope was crushed in 1988 by the reintroduction of foreign films into the Korean market. The Republic of Korea had a longstanding ban on foreign films as a way to develop its national film industry, but the lift of this ban immediately flooded Korean cinemas with Hollywood films. From 1990 to 2000, foreign films consistently had a far larger market share than Korean films. In addition, as imports increased, domestic productions decreased drastically.

The final major change in the history of Korean cinema was the entrance of private companies as investors and producers. In the 1990s, Samsung would become the first chaebol (kor: 재벌) to enter the Korean film industry, once again changing the landscape. Film production, which was originally split among various teams and companies, would now be consolidated under one company that would handle financing, producing, and distributing. The private takeover of film production increased general funding and production of films in Korea, but at the same time, profit margins would become more important as well. According to some directors, this led to a divide between the ‘auteurs’ of independent film and the large companies that prioritized revenue and commercially safe options.

This history perfectly explains the environment in which a film like Bong’s Parasite could reach such great success. Its production is a culmination of Korean film history including the work of dedicated directors, investment by major companies, and the intervention of the government. In addition, Bong continues the legacy of using film as a major tool for social change, with Parasite being an entertaining and biting commentary on ever growing economic disparities in the Republic of Korea. Bong himself cited many renowned Korean films as important influences on his work, so, in a way, his work is a love letter to Korean cinema as a whole.

However, there is one major change that could come from Bong and Parasite’s win: the exposure of Korean cinema to an international audience. A small number of Korean films have received international praise and success, most notably director Park Chan Wook’s Vengeance Trilogy, but Parasite’s immense popularity introduced millions of people worldwide to Korean cinema. As people become more curious about Korea’s major releases, Korean films have been winning awards at major international film festivals and getting wide releases abroad.

Clip from Paraiste, 2019

Of course, there is also a need domestically for the production of high quality films. Film is one of the most important media for sharing nuanced and meaningful stories and shedding light on major social issues. Considering Korea’s long and complex history as well as the various issues that exist in modern society, Korean filmmakers perform an important role by sharing their nation’s history and society. One example of this is Chun Taeil (kor: 태일이), an animated film that was released in 2021. It follows the real life story of Chun Taeil, a workers rights activist whose capture and murder by the police was a major event for the Democraticization Movement in the 1980s. By retelling this specifically Korean story for a Korean audience, it inspires political awareness among young people and reminds the population of the importance of the Democratization Movement in our modern lives. There is also the 2011 film Silenced, which recounted real incidents of abuse of deaf students. The film was a massive success and brought massive amounts of attention to the issue of abuse and even led to changes to legislation to protect minors and disabled people from abuse. Even films that do not speak on specific events in Korean history, such as acclaimed director Hong Sang Soo’s 2019 film The Woman who Ran, speak on larger existential themes and explore the ways humans communicate with a Korean lens. The films listed above, as well as all those a part of Korean film canon, together give us insight on Korean life, culture, and history. There is therefore a need to support and develop Korean cinema as a way to share new perspectives on Korean life and identity. Hopefully the export of Korean films overseas will only increase the prestige of Korean film and uplift new voices.

Chun Tae-il, 2020

Written by: Curtis Feldner

Originally from Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Currently a 4th Year undergraduate pursuing a BS in Educational Studies at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Exchange student at Korea University and intern at VANK (Voluntary Agency Network of Korea)