Even if you are not an expert on Korean history or culture, I am almost positive that you have heard of K-Pop, Korea’s popular music. I am sure you have at least caught a glimpse of the flashy costumes and hair dyed in every shade of the rainbow, have watched the sharp and precise dance moves, and have heard the catchy beats that seem to just stick in your head for days on end even though you may not have the slightest idea what they are saying.

However, if K-Pop and other popular music has been your only introduction to the Korean music and performance scene, I am here to tell you that you are missing out on something so much larger than just popular music, and that there is so much more that is worth exploring.

The fine arts are such an irreplaceable and unique part of a nation’s culture and history. Where spoken words and other actions may fall short, song, dance, art, and drama are just another means by which a nation’s people can express themselves, and from their roots these arts continue to evolve into something beautiful and everlasting.

So while K-Pop and subsequently trending TikTok dances may be what some people consider to be the trademarks of modern Korean society and its performance industry, I think it is more than worthwhile to take a look farther back into some of the Republic of Korea’s most astounding and breathtaking performances, what one may be able to claim as the very root of the sound of Korea today.

There is, of course, a plethora of music and performance genres that I could delve into and write about for hours, but for this article I will focus on the performance of samulnori (사물놀이), arguably one of the music genres that best encapsulates the “traditional” sound that we associate with the Republic of Korea.

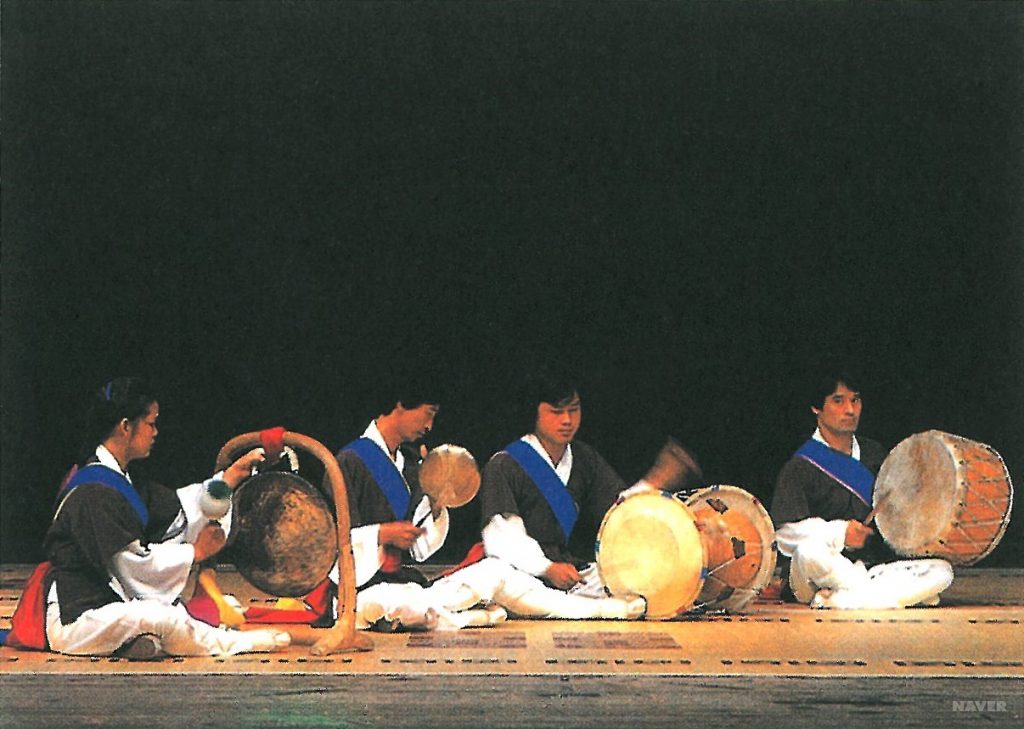

A typical Samulnori

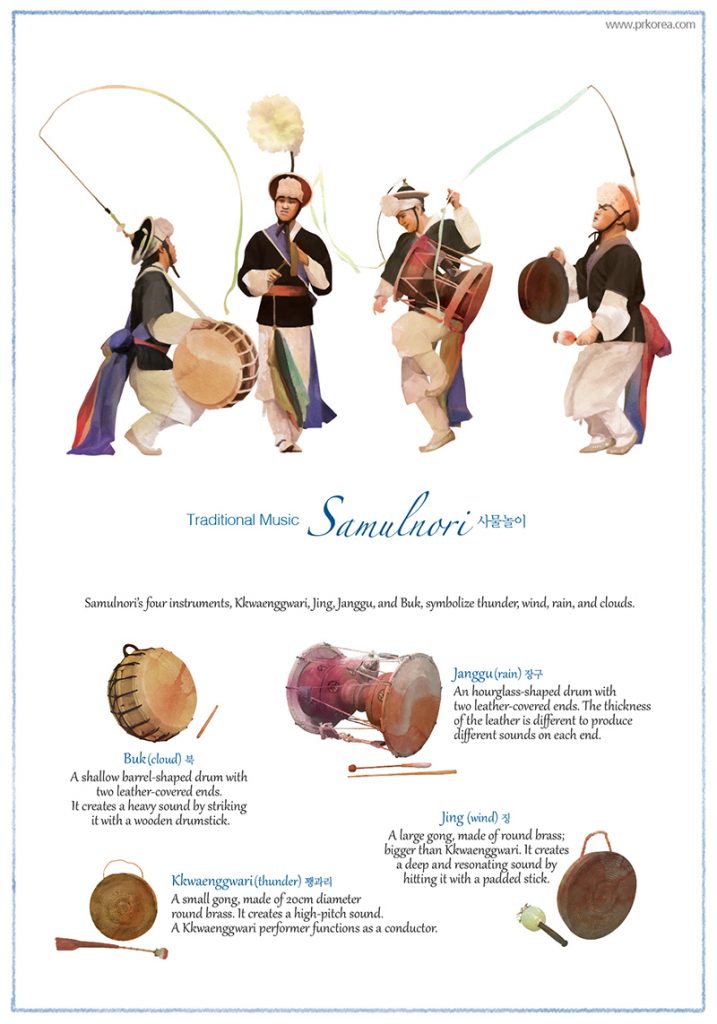

Samulnori is a fun and loud percussion performance, almost coming off as chaotic to a first-time listener. There are only four instruments used, all different genres of percussive instruments that each give off their own unique sounds. The term samul means “four objects,” while nori means “to play,” the entire word quite literally describing the construction of this music genre.

The music genre of samulnori is actually relatively new to the music scene in comparison to other genres. While the genre of samulnori has evolved from other types of folk music, the specific performance of samulnori was not showcased until 1978, when a group of four musicians, Kim Deok-su (김덕수), Lee Jong-dae (이종대), Choi Tae-hyun (최태현), and Choi Jong-sil (최종실), performed for the very time under that specific name.

The four instruments being referred to in the term samulnori are the jing (징), buk (북), janggu (장구), and ggwaengwari (꽹과리). Each instrument plays a very specific role in the overall samulnori performance, utilizing their unique sounds and playing styles to create a performance that is so multi-layered, it is almost difficult for listeners to choose where to focus their attention first.

jing and ggwaenggwari

The jing is a medium-sized gong that emits a low and drawn out tone when struck, reverberating long after being hit and creating a solid backbone for the overall performance. Opposite of this is the ggwaengwari, which is a smaller handheld gong that emits a high-pitched, almost piercing, clang when struck. Whereas the jing maintains a steady tempo that remains constant for nearly the entire performance, the ggwaengwari’s shrill sound is rather sporadic in its appearance, appearing to follow no rhythm at first only to then fall in line with its fellow performers. If one were to characterize the ggwaengwari as they would a person, I feel that the term “free-spirited” would be most fitting, compared to the jing that could be best described as “reliable.”

buk and janggu

The two remaining instruments, the buk and the janggu, are both types of drums, similar in role but extremely different in sound. The buk is probably best described as a small bass drum, its sound comparable to the rolling claps of thunder that come with springtime storms. In comparison, the janggu has a much “lighter” sound, something that is a bit more muted than the buk but still just as cutting and clear. In my opinion, out of all the instruments used in samulnori, the janggu is the most diverse in function and sound, and the performers of the janggu seem to have one of the more difficult tasks. For one, the janggu is a double-headed drum that resembles an hourglass, with the players wielding a stick in each hand to strike each side of the drum accordingly. If you watch a samulnori performance, you can actually see how the performers use one hand to strike one side repeatedly while their other hand flips back and forth between the two sides, making for both an entertaining show of skill and a more enthralling flow of rhythm. They can also manipulate the sounds and vibrations that come from the drum by adjusting the strings in the center of the instrument, creating sounds that range from very heavy and muted to light and sharp, a unique feature amongst the other three instruments that are limited or completely fixed in terms of pitch.

While each instrument has its own unique sound and role, all four come together in a perfect blend to form the very distinct and harmonious sound of samulnori.

The samulnori performance has been described as revolving around the concepts of tension and relaxation, with the most important parts being the breaths that are taken in the middle. The performance starts off at a very slow tempo, led by the buk, and eventually speeds up into something exciting and thrilling that makes your heartbeat quicken and pound with each hit of the drums. The rhythm is an ever-changing flow of sound, barely giving listeners enough time to process the patterns they are hearing before they evolve into something new. It is an almost overwhelming experience, so many sounds and rhythms and beats flooding your head at once at a dizzying speed.

That is exactly what makes the concept of “breathing” so important. In a performance that is as fast-paced and free-flowing as samulnori, the moments where the sounds fade out and we are left only with the slow beat of the buk or the muted tinkling of the ggwaengwari, these are treasured moments of respite. It is a sensation similar to stepping into the eye of a hurricane, a moment to finally breathe before being thrown right back into the beautifully organized chaos.

This focus on tension and relaxation makes for a truly gripping performance, one that will keep you on the edge of your seat for its entire duration. Of course, the best way to truly experience the sounds and emotions of samulnori would be to watch a performance for yourself, whether that be live or via the internet where there are more than a few recordings of this breathtaking art. The interpretations of every art form are different for each person, with the most important thing being the listener’s ability to truly take in everything that is being presented to them and make it their own, mixing the music with their own emotions and thoughts to make something truly unique to them. I hope that the information in this article can act as a sort of baseline for you for the next time you watch a samulnori performance, and that it is able to provide some insight on this beautiful piece of Korea’s music culture.

To help you get started on your samulnori listening experience, you can check out the following performance by a group of high school students.

Written by : Allison Garbacz

From Illinois, United States. Current 5th-year undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, B.A. Candidate for Linguistics, B.A. Candidate for Asian Languages and Cultural Studies, Exchange student at Korea University, Intern at VANK (Voluntary Agency Network of Korea)